Interview with Patty Leinemann

Patty Leinemann completed her bachelor’s degree in fine arts at UBC Okanagan after years at a desk; on dance floors, yoga mats, theatre chairs and winding roads; and being hands-on from dead-heading to a current exploration of analog collages. She continues to search for what she wants to be when she grows up.

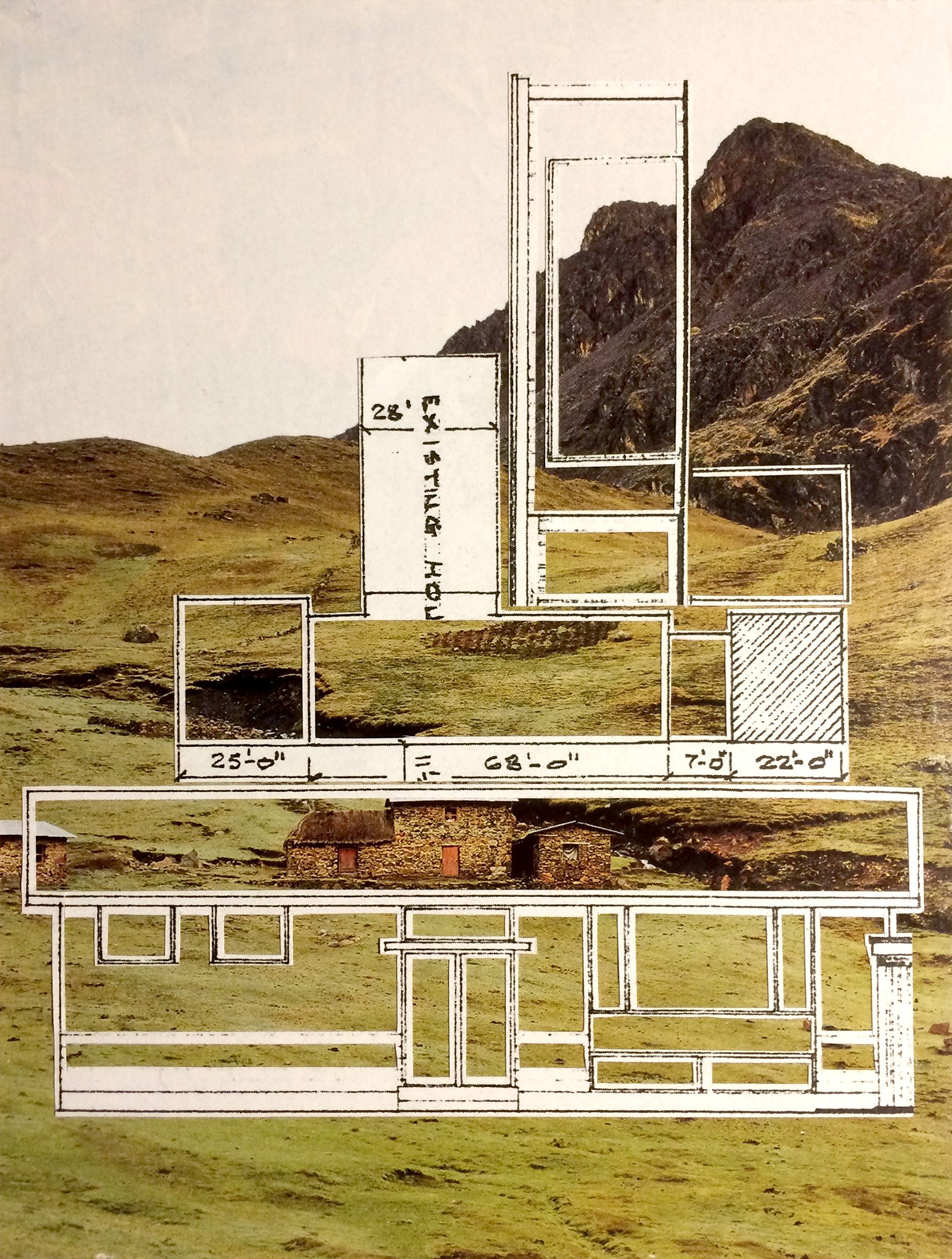

Patty Leinemann, The House That Paul Built, 2023, analog collage.

Kolton Procter: I reached out to you in the summer of 2020 to see if you would be interested in writing something for Found You Magazine, the theme being home. Upon delivery of the first draft of your story “Farsightedness,” you said “it was a healing piece to write.” If you can remember, could you walk me through your thought process? How did you land where you did with this piece?

Patty Leinemann: The summer of 2020 [sighs] I was riddled with angst and anger, trying to come to terms with our altered world. Five months had passed with continued lockdowns at long-term care facilities. Five months of not being able to visit and assist my father! And we still had a long way to go, didn’t we?

In hindsight, your invitation to write was a gift. At first, my writings were drenched with that anger. I could not find a way to shift it. Yes cliché, time does heal, but this time helped with each rewrite after rewrite after rewrite. The process calmed my chattering mind. I explored how to link the magazine’s theme between my father’s long-term care “home” and me living in the house that he built. What an epiphany when the answer arrived one day while outside on the homestead. I stood motionless, my breath held. That’s all I can share until the magazine’s release.

KP: Initially you followed up with some photographs you took of your father Paul for consideration to include with the piece which in the end we made the decision to omit from print. I find these images to be intense and extremely vulnerable. Could you describe what is happening in these photographs?

Patty Leinemann, True Grit (series), 2014, photographs.

PL: [Sighs] Rewind. 2014. This series of black-and-white photographs captured the moment my father realized that he could no longer stand. He is in a wheelchair, grasping and rattling the railings on his medical bed in his new room that he arrived in a week earlier. He is lurching back and forth, trying to pull himself up. His breathing escalates with each rattle. He calls out that he cannot do it and slumps in his chair. This is so layered for me. Honestly, being with him that visit behind the camera gave me a shield to the raging emotions. How could I be so cold to be snapping photos as he struggled? Capturing this devastating realization for him is one of those imprinted molecular moments for me. I’m right there in that room, with every unsettling sensation. Yet, what still startles me is that when I showed my father the photographs afterwards, he named the series True Grit. That’s my dad.

KP: What is your relationship with these images? How did they come to be and how do you see them in relation to the story you’ve shared for the issue?

PL: I was in my second year of university. For a class project, I wanted to photograph the effects of the medication my father was taking for his Parkinson's. After presenting my idea to him, he agreed to be photographed. But this plan ended abruptly when he fell at home a couple days later which led to a transfer to the long-term care facility. The staff encouraged our family to not visit for six weeks for him to settle in. What? I broke the rules immediately! What an introduction to this new place he would now have to call home. Oh the challenges and lessons we encountered over the next seven years. My father always told me, “home is where you hang your hat.” And so began my story.

KP: We decided to go with a different visual element to your section and landed on the use of red thread weaving across the pages in curves and loops. You hand-stitched red thread around the text on the page. Why did you land on this treatment and what is the significance of red thread for you in your work?

Patty Leinemann, creative process shot, 2023.

PL: Red thread is about connection for me. An invisible thread we have between ourselves and people, places, experiences, memories, emotions. Simply, life. And I love red. Recently I began sewing into my analog collages. For your magazine, the motion of the stitching symbolizes a journey which my father and I certainly were on. This final detail also honours a piece of my mother who taught me to sew. There’s a lot of love in those stitches.

KP: It’s been three years since you sent me the first draft of “Farsightedness.” I wonder, has your relationship with the story changed over time? What is it like to reflect on it now?

PL: I have to rewind here too. I was always tripping over my feet as a child. No one thought to check my eyes until a public health nurse diagnosed me with farsightedness in Grade 1. I could see far, but not near. That’s how I felt as I wrote. I just could not see what I was dealing with until the end of the story. Since writing “Farsightedness,” it has become more meaningful. My father handled most things at the long-term care facility with far more grace than me before he left this world.

When you recently asked if any edits were needed on the piece, I had to wait a day to reread the story. I wasn’t sure how I would react. It’s been over a year since my father’s passing, and the grief cycle has its own journey. I was surprised that the writing stands. I didn’t change a word. ● All works courtesy of Patty Leinemann.